1

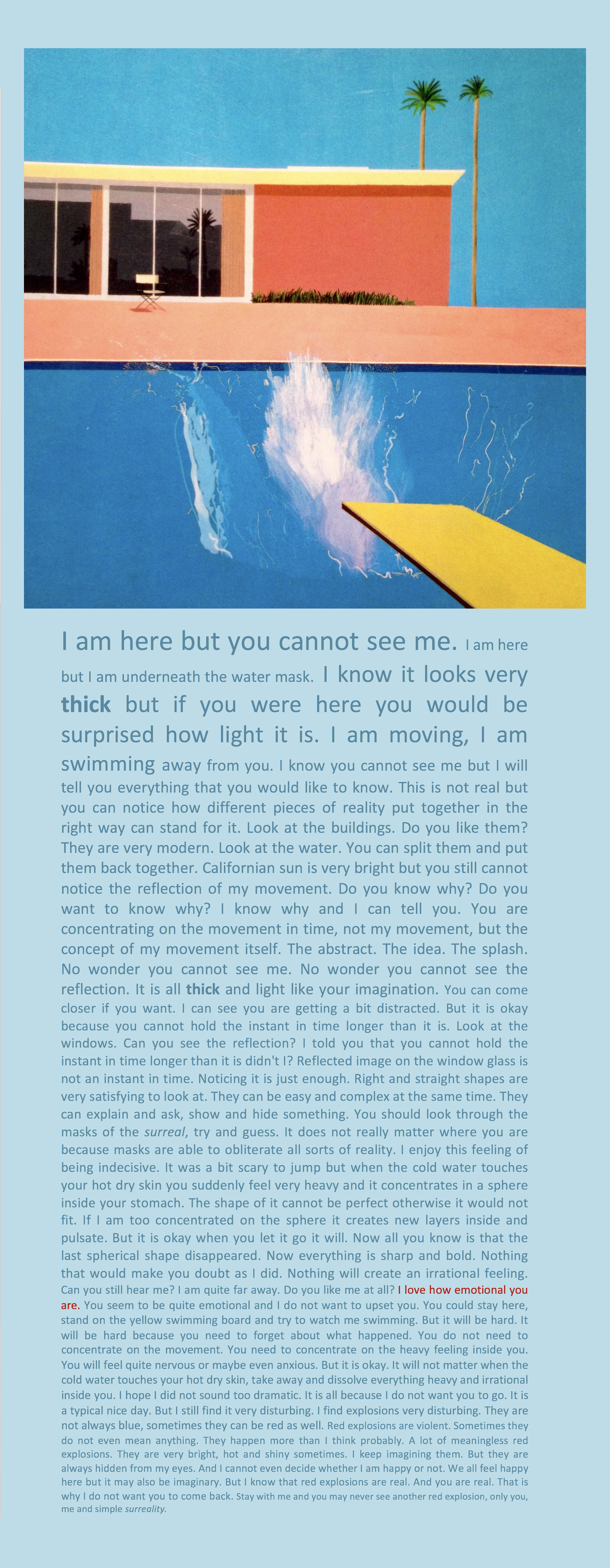

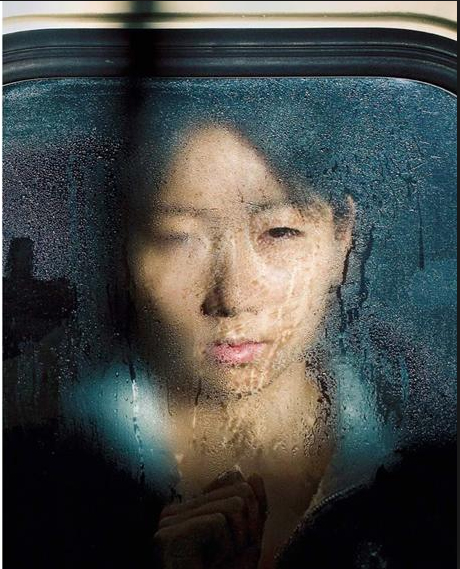

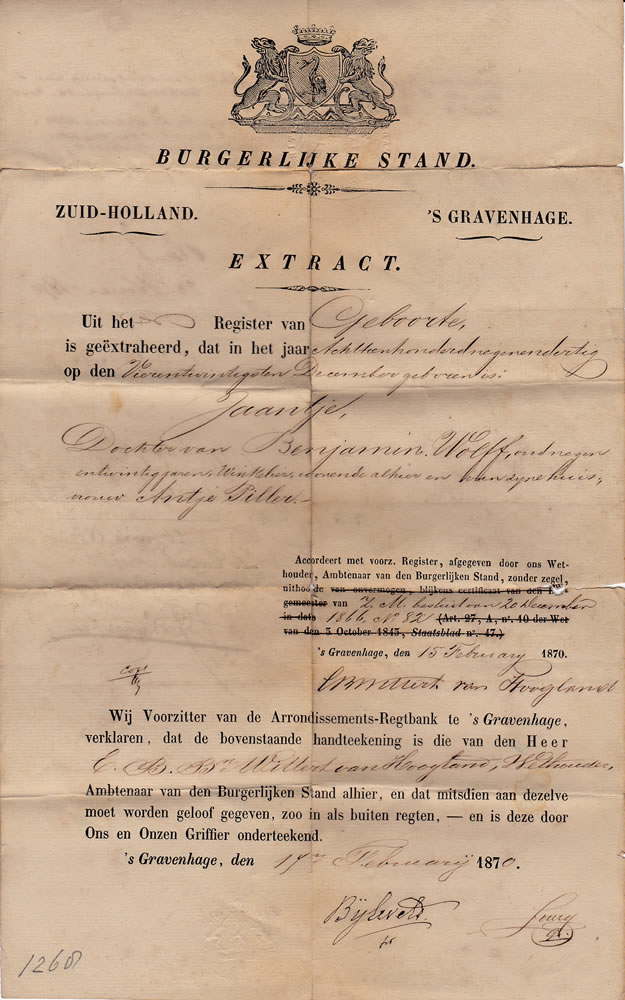

The brown certificate with its notices and crossings-out

its crisp fonts and faded signatures

Dutch, not French ‒ we knew this ‒

words waiting for translation

safely folded inside a striped, brown

card store bag ‒ brittle with age

guarding history

The brown paper did not certify a birth

but rather authenticated the certificate of a birth

prepared for immigration

carrying signatures of the Consul General for Aliens

signatures of other civil servants based in Paris

guaranteeing other signatures

(This we knew. This we surmised.)

2

“This Dutch girl, Jeanne Wolf, had brothers in Paris,

but were looked very much down on,

as being cheap tradesmen”

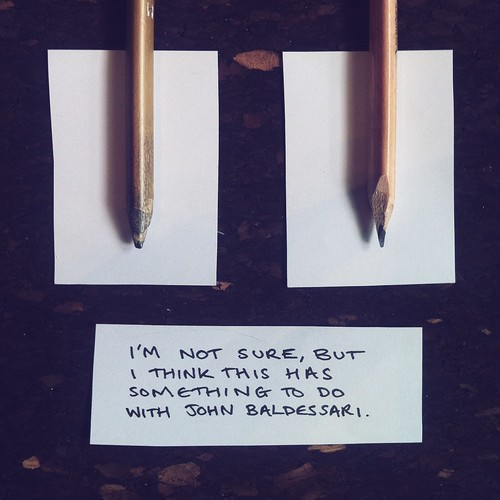

penciled words in 1942

written on yellowed backs

of Uniform Standard New England Forms No. 648

Smoke Endorsement No. 1

Stipulations, Limitations, and Conditions Applicable to Smoke (10-38)

footstep to a future we didn’t know

3

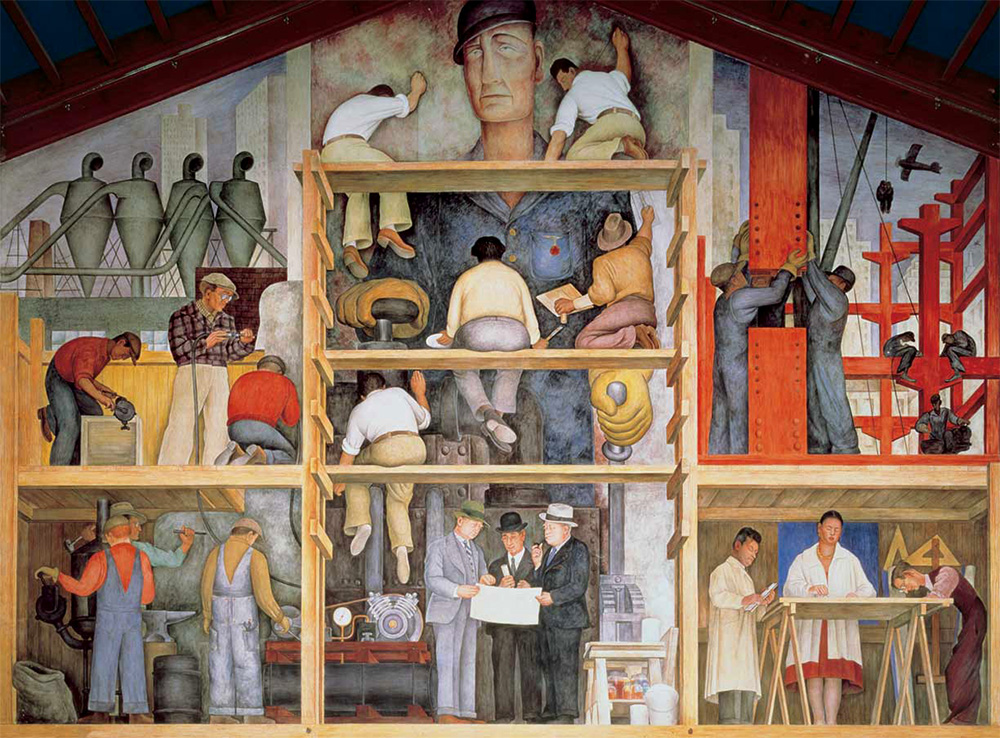

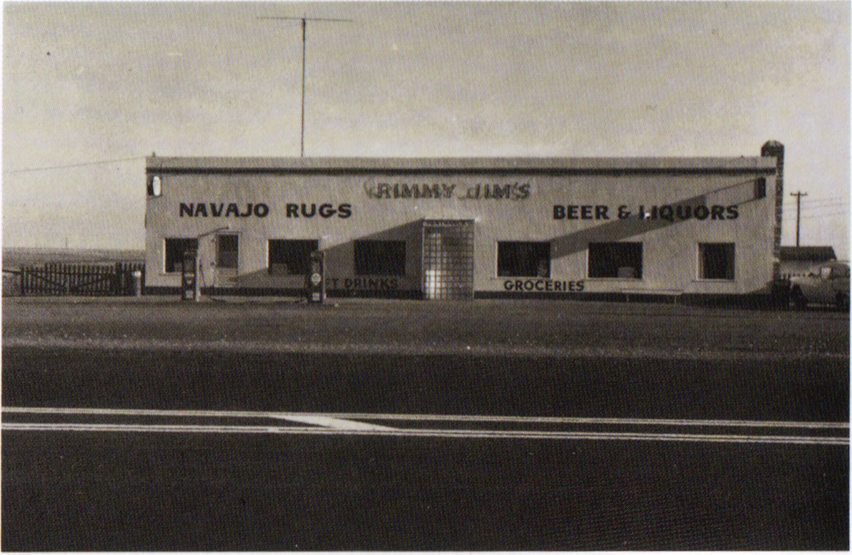

Late-19th and early-20th-century vernacular architecture also occurs along Clinton Avenue east of

Piermont Avenue. Two to two-and-a-half-story three-bay by two-bay residences with front porches are located at 40, 44 and 50 Clinton Avenue. These residences provide a rich visual counterpoint to more high-style architecture along the road east of Piermont Avenue. . . . ‒Allison S. Rachleff

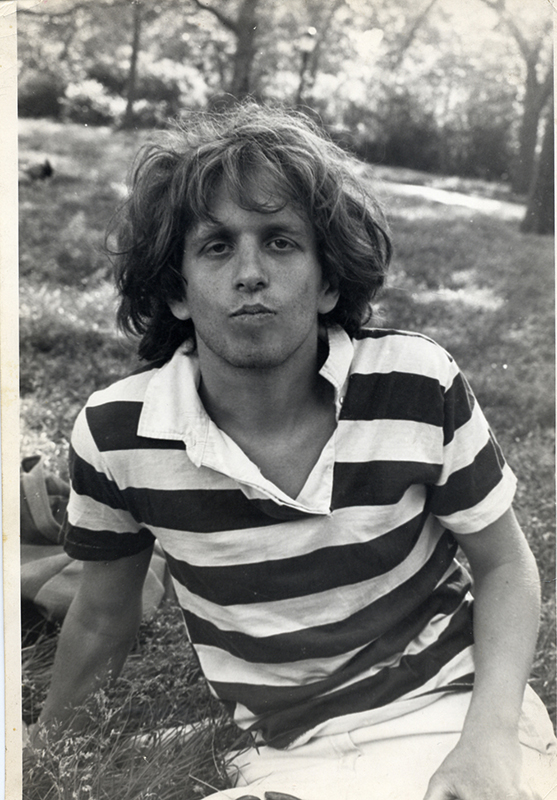

We lived at number 50 ‒ not rich, not poor

It’s the 1950s and the family

secure in its colonial Protestant identity

linked to Presidents

(though not all are the good ones)

lives on a street of mixed ethnicity

where children play baseball in the street

and all the parents rush out of their houses

to break up the fights

and the children do not date

once the baseball games conclude

but rather

seek their own kind

at separate lunchroom tables

and the father comes home from the ecumenical

breakfast at the synagogue and says

“I had the most curious roll this morning

It’s called a bagel and it was tasty.”

4

Jeanne Wolf safe in America died of consumption

in 1883 at 44 in New Bedford, Massachusetts

her husband died at 45 in 1889 in Philadelphia

their two sons also dead before their 40th birthdays

one dying mysteriously in New Orleans,

the other of consumption in Oran, Algeria.

(This we knew. This we surmised.)

5

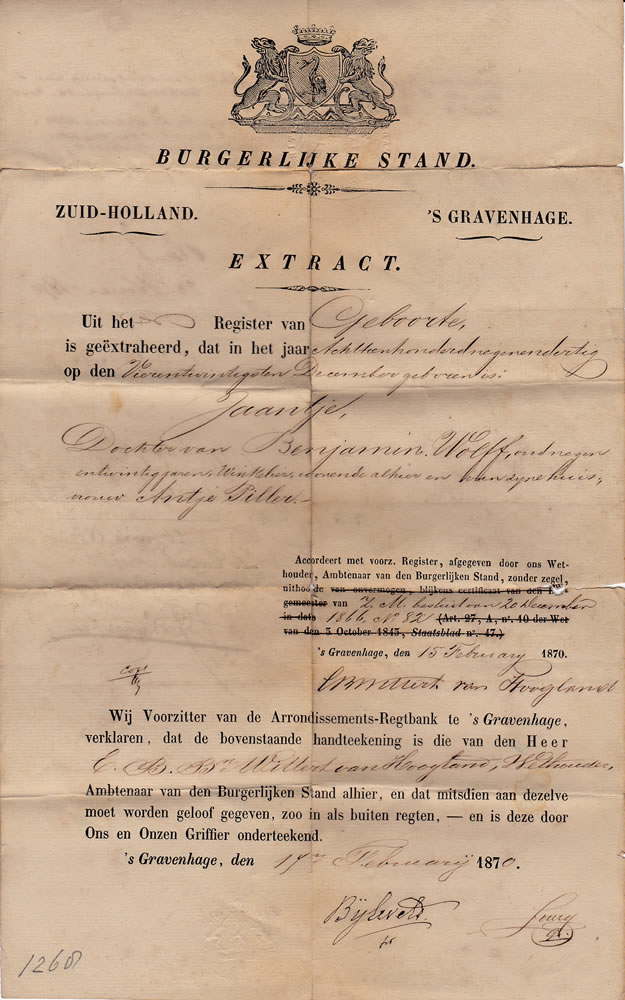

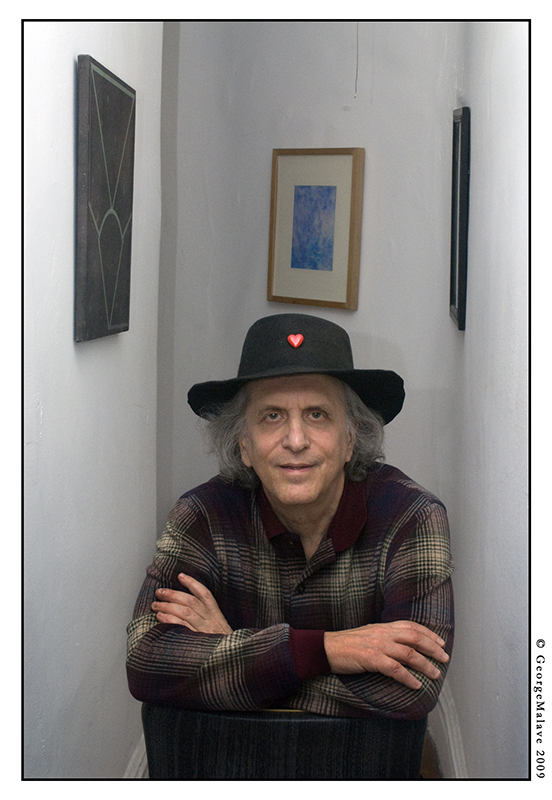

A nephew long lost to us was found

in Colorado with DNA. He wrote,

“I am curious about what appears

to be our Sephardic Jewish roots.

Was Grandpa’s mother Jewish?”

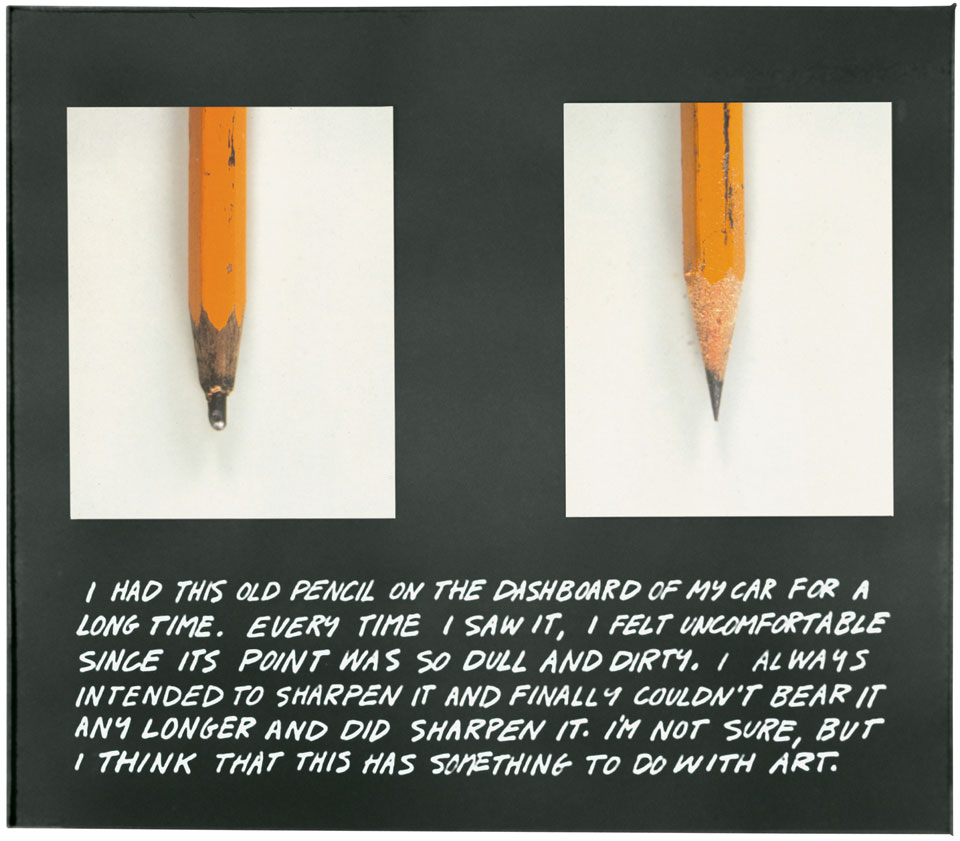

armed with dictionary

devoid of idiom or grace

the birth certificate gave up its dates

its names

its towns

and occupations

From the Register of Births

is extracted that in the year 1839

on the twenty-fourth of December was born

Jeanne

Daughter to Benjamin Wolff, 29 years old

shopkeeper resident here [Zuid-Holland, Gravenhage]

with his housewife, Antje Pillar”

and a cousin we’d never met

from Brooklyn and Massachusetts

found our Dutch family group

All living in 1942

all dead in Poland by 1944

(Our Mayflower descendant’s note

“cheap tradesmen” ‒ code for Jew)

Betje Piller, an aunt, age 86

Alice Blitz, her grandchild and our cousin, age 20

an entire family line erased

Sobibor, Auschwitz

Relatives we did not know

captured, killed

in a family where ‒

safe across the ocean ‒

my memory of World War 2

was falling down a wooden staircase

bouncing on the landing

turning, sprawling

howling in the dark

of an air raid drill at night

Uncles sent off to war returned

(a cousin did not ‒ a rare

long-distance phone call

sticks in my mind ‒ distress)

brown paper

crisply folded into a striped brown bag that held

the birth certificates and a promissory note

left for us to preserve our past

footstep to the future

leading to the day

when “they”

became “us”

Martha Deed October 12, 2016

References:

Allison S. Rachleff. South Nyack [New York] Historic District. October 2005, Revised 2011.

https://www.erfgoedleiden.nl/collecties/personen/zoek-op-personen/weergave/akte/id/ab091c0b-bad6-83c5-8789-a91581b8b68c